Humans - men in particular - have a fascination with speed that is so universal that it must be genetic (probably the same gene that makes dogs stick their heads out of car windows). Coming of age in the 1970s, it was a rite of passage among my gearhead high school crowd to take our cars to a lonely stretch of highway and try to peg the speedometer. This was foolish beyond the chance of losing your license; the cars we were driving had crumby bias ply tires, stone-age aerodynamics and 120 mph speedometers. North of 80 mph the front of the car would start to lift and the steering got a funny disconnected feel; pushing past that was more aiming than driving. The only reasons any of us survived this stupidity were optimistic speedometers and a willingness to lie about how fast we actually went before backing off.

In the fall of 1947 a much higher stakes version of this game was playing out at the Muroc Army Airfield (soon to be Edwards Air Force Base) in the California dessert. Two experimental aircraft, both supersonic capable, were being flight tested by two distinctly type-A pilots.

Welcome!

Twisted from the Sprue is my little corner of the internet. This site started as a simple web presence for the Three Rivers IPMS model club - as in middle-aged guys who never quite out-grew gluing together miniature cars and planes (and not a club of really good looking people who have their pictures taken for underwear ads and the like). The club now has a real web-site, and this blog is a place for me to post stuff I find interesting or just want to ramble on about.

Don

Its reassuring to know you're not the only guy with an obsession for trivia - if you happen across something interesting here, or have a question or something to contribute, please leave a comment or drop me an email at dnschmtz@gmail.com

Don

___________________________________________

Showing posts with label Aviation. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Aviation. Show all posts

Tuesday, June 10, 2014

Wednesday, December 5, 2012

For conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity...

When it comes to heros, I've always liked Halsey's famous quote:

“There are no great men. Just great challenges which ordinary men, out of necessity, are forced by circumstance to meet.” - Admiral William Halsey

If you read the citations of those receiving the Congressional Medal of Honor, you find that most were given (often posthumously) to someone just looking to keep their head down, who ended up between the proverbial rock and a hard place and chose to put the lives of their fellow soldiers ahead of their own. Read the story of Marine private Harold Agerholm and Navy corpsman Donald Ballard and you'll understand what I mean.

And then there are the men who take insane risks taking the fight to the enemy for no rational reason.

William Shomo grew up in western Pennsylvania, in the small city of Jeannette, about 30 miles east of Pittsburgh. Unless you live nearby, Jeannette is just another high school football score scrolling across the Friday night news or an exit sign on Route 30; in the 1930s it was a bustling manufacturing town, churning out home goods for the region and turning steel into industrial machines. Shomo graduated from Jeannette High School in 1936, went off to the Cincinnati Mortuary School for 3 years, came home to Jeannette with his embalmers license and went to work at the Miller Funeral Home.

In the summer of 1941 Shomo joined the Army Air Force. Since no one has ever written an in-depth biography of Shomo's life, we can only guess as to his reasons. At the time it was already obvious the U.S. would soon enter the European war, and with the draft cranking up Shomo may have figured that it was better to join on his own terms - before the massive call up that would come when the shooting started. Shomo was in the right place at the right time: the Air Force (still part of the Army) was undergoing a massive build up of men and aircraft; somehow Shomo became a pilot.

Shomo then disappears from the pages of history until late 1943 when he turns up in the Pacific, attached to the 82nd Tactical Reconnaissance Squadron in New Guinea where he is flying photo-recon and ground attack missions. The 82nd is outfitted with already obsolete P-39s and P-40s: they fly low over well defended enemy locations, make a few strafing runs to distract the anti-aircraft gunners and then circle taking photos. While Shomo is technically a fighter pilot, the only time he sees a Japanese plane is while he is on the ground and they are trying to drop bombs on him, which is probably just as well as the planes he is flying are largely outclassed.

In December of 1944 Shomo's squadron receives F-6Ds - P-51s with a big hole cut in the side of the fuselage for the camera to look out. Shomo gets an early Christmas present on December 24th, when he is put in command of the squadron and transfered to Mindoro island in the Philippines, just in time to help MacArthur keep his promise to return. On January 9th, as 175,000 men of the 6th Army come ashore at Lingayen Gulf, Shomo leads his first combat mission in the F-6; while photographing Japanese airbases on the main Philippine island of Luzon he catches a Japanese Val as it comes in for a landing and earns his first "kill" of the war.

Two days later things get a lot more exciting. Shomo and his wingman, Paul Lipscomb are on their way to photograph Japanese airbases again when they spot a gaggle of Japanese planes overhead - a "Betty" bomber escorted by 11 Ki-61 "Tonys" and 1 Ki-44 "Tojo" fighters. Shomo doesn't hesitate; he channels his inner Tom Cruise and orders an attack.

There are many conflicting accounts of what happens next; the details that follow are based largely on Shomo's Medal of Honor Citation:

The Japanese pilots have likely never seen a Mustang before - from 2000 feet above the P-51s look a lot like two more Ki-61s joining the formation, and several Japanese pilots waggle their wings in greeting. Taking fulll advantage of their confusion, Shomo closes to rock-throwing distance and shoots down three Ki-61s in quick succession as he cuts through the formation, then fires on the Betty from below, sending it toward the ground on fire, still escorted by two Ki-61s. By this time a few of the Japanese pilots have figured out what is happening and try to counter-attack; Shomo shoots down a Tony in a head-on encounter and then exchanges fire with the Tojo until it disappears into the clouds.

Meanwhile the Betty has crashed, leaving two Tonys below; Shomo dives on them and shoots them down too - making 7 kills. The two remaining Tonys decide they have had enough and bug-out. The engagement lasts all of 6 minutes; somewhere around the halfway point Shomo has become an Ace. While Shomo has been busy, Lipscomb has shot down 3 Tonys of his own.

It was the sort of story no one would have believed, except both pilots had really good cameras...

“There are no great men. Just great challenges which ordinary men, out of necessity, are forced by circumstance to meet.” - Admiral William Halsey

If you read the citations of those receiving the Congressional Medal of Honor, you find that most were given (often posthumously) to someone just looking to keep their head down, who ended up between the proverbial rock and a hard place and chose to put the lives of their fellow soldiers ahead of their own. Read the story of Marine private Harold Agerholm and Navy corpsman Donald Ballard and you'll understand what I mean.

And then there are the men who take insane risks taking the fight to the enemy for no rational reason.

William Shomo grew up in western Pennsylvania, in the small city of Jeannette, about 30 miles east of Pittsburgh. Unless you live nearby, Jeannette is just another high school football score scrolling across the Friday night news or an exit sign on Route 30; in the 1930s it was a bustling manufacturing town, churning out home goods for the region and turning steel into industrial machines. Shomo graduated from Jeannette High School in 1936, went off to the Cincinnati Mortuary School for 3 years, came home to Jeannette with his embalmers license and went to work at the Miller Funeral Home.

In the summer of 1941 Shomo joined the Army Air Force. Since no one has ever written an in-depth biography of Shomo's life, we can only guess as to his reasons. At the time it was already obvious the U.S. would soon enter the European war, and with the draft cranking up Shomo may have figured that it was better to join on his own terms - before the massive call up that would come when the shooting started. Shomo was in the right place at the right time: the Air Force (still part of the Army) was undergoing a massive build up of men and aircraft; somehow Shomo became a pilot.

Shomo then disappears from the pages of history until late 1943 when he turns up in the Pacific, attached to the 82nd Tactical Reconnaissance Squadron in New Guinea where he is flying photo-recon and ground attack missions. The 82nd is outfitted with already obsolete P-39s and P-40s: they fly low over well defended enemy locations, make a few strafing runs to distract the anti-aircraft gunners and then circle taking photos. While Shomo is technically a fighter pilot, the only time he sees a Japanese plane is while he is on the ground and they are trying to drop bombs on him, which is probably just as well as the planes he is flying are largely outclassed.

In December of 1944 Shomo's squadron receives F-6Ds - P-51s with a big hole cut in the side of the fuselage for the camera to look out. Shomo gets an early Christmas present on December 24th, when he is put in command of the squadron and transfered to Mindoro island in the Philippines, just in time to help MacArthur keep his promise to return. On January 9th, as 175,000 men of the 6th Army come ashore at Lingayen Gulf, Shomo leads his first combat mission in the F-6; while photographing Japanese airbases on the main Philippine island of Luzon he catches a Japanese Val as it comes in for a landing and earns his first "kill" of the war.

Two days later things get a lot more exciting. Shomo and his wingman, Paul Lipscomb are on their way to photograph Japanese airbases again when they spot a gaggle of Japanese planes overhead - a "Betty" bomber escorted by 11 Ki-61 "Tonys" and 1 Ki-44 "Tojo" fighters. Shomo doesn't hesitate; he channels his inner Tom Cruise and orders an attack.

There are many conflicting accounts of what happens next; the details that follow are based largely on Shomo's Medal of Honor Citation:

The Japanese pilots have likely never seen a Mustang before - from 2000 feet above the P-51s look a lot like two more Ki-61s joining the formation, and several Japanese pilots waggle their wings in greeting. Taking fulll advantage of their confusion, Shomo closes to rock-throwing distance and shoots down three Ki-61s in quick succession as he cuts through the formation, then fires on the Betty from below, sending it toward the ground on fire, still escorted by two Ki-61s. By this time a few of the Japanese pilots have figured out what is happening and try to counter-attack; Shomo shoots down a Tony in a head-on encounter and then exchanges fire with the Tojo until it disappears into the clouds.

Meanwhile the Betty has crashed, leaving two Tonys below; Shomo dives on them and shoots them down too - making 7 kills. The two remaining Tonys decide they have had enough and bug-out. The engagement lasts all of 6 minutes; somewhere around the halfway point Shomo has become an Ace. While Shomo has been busy, Lipscomb has shot down 3 Tonys of his own.

It was the sort of story no one would have believed, except both pilots had really good cameras...

Within a few months, word of Shomo's daring do made it up through the ranks. Shomo was promoted and put up for the Medal of Honor, which he received in April. He would go on to a long Air Force career, including a stint as commander of the 54th Fighter Group, based at Pittsburgh International Airport. Shomo died in 1990, and is buried in St. Clair Cemetery in Greensburg.

Modeling Shomo's F-6 and Who Was Snooks?

My research into Shomo's career was driven by a very unexpected bit of luck last summer at the IPMS Nationals raffle: on the next-to-last ticket drawn I won Tamiya's latest 1/32 Mustang super-kit. I was very tempted to sell the kit to someone who could do it justice, but the kit had been donated by Hobby Link Japan, which meant it was a Japanese market kit with no shrink wrap to break... I popped open that big box, scoped out the sprues and instructions and started to drool. On a whim I did a few internet searches for western Pennsylvania Mustang pilots and found Bill Shomo's amazing tale, and I knew there would be no rational thinking involved: I had to build the kit as Shomo's F-6.

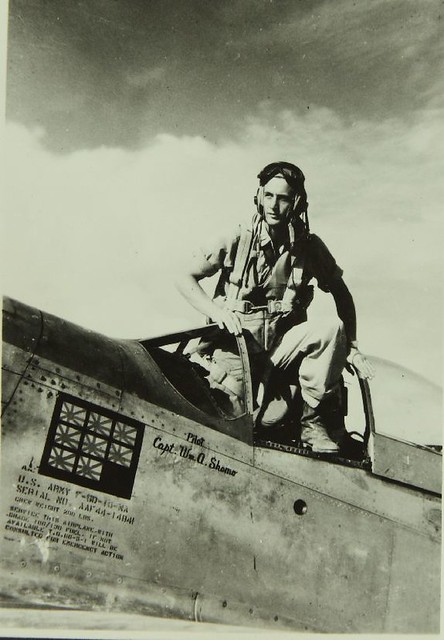

A few more web searches turned up a few good pictures of Shomo's plane. Or rather, planes... Shomo's plane on that fateful January day was a well worn F-6D-10, serial number 44-14841. A few months later, another pilot borrowed this plane for a mission and didn't return. Meantime, Shomo was given a shiny new Mustang, dolled up with black-and-gold stripes and "The Flying Undertaker" on the nose; the perfect backdrop for picture taking when Shomo received his Medal of Honor.

But the F-6 was the plane that was there. A few more web searches turned up a set of Kageroo decals with the right markings, including the 8 kill markings shown in the picture above. The F-6 had a big bezel on the port-side holding a dinner-plate sized window for the reconnaissance camera, but that seemed within my scratch building abilities. And then I found a picture of the starboard side of Shomo's F-6 with the stylized yellow text reading "Snooks - 5th", which is not on the Kageroo decal sheet. What the heck? Back to Google...

It turns out most of Shomo's planes had "Snooks" on the nose (at least the ones he kept long enough to paint). "Snooks" was the nickname of crew chief Ralph Winkle's wife. The photo of the plane accompanying the decals was taken before or just after Shomo and Winkle took possession of the plane, but there are a number of photos of the plane with the trademark name on the nose. Even the flashy "Flying Undertaker" plane carried "Snooks - 6th" on the starboard side. By the way, a lot of internet pictures of Shomo's plane include Ralph Winkle, and some misidentify Ralph as Bill Shomo; in 1945 Ralph was stocky, well tanned, often shirtless and had a fairly bushy haircut, while Shomo was tall, skinny and surprisingly pale for someone lliving in the South Pacific.

My daughter the graphic designer turned photoshop loose on the picture and extracted the "Snooks - 5th" marking and scaled it to the right size for printing on decal paper; four years of art school tuition finally paid off! Now all I have to do is build the model. Stay tuned; I'll post pictures as the build progresses, but this article has gone from long to ridiculously long, so I'm signing off for now.

One last thing: if you haven't figured it out by now, I love Pittsburgh area history; if you have any details on William Shomo's life or career, I'd love to hear from you.

Tuesday, June 19, 2012

The Right Stuff Story You Haven't Heard

If you read Tom Wolfe's book, The Right Stuff, or watch the movie version, there is a scene right at the beginning where Chuck Yeager is given the job of flying the X1, replacing greedy civilian test pilot and playboy "Slick" Goodlin, who is holding the project hostage by demanding lots of money to attempt to break the sound barrier. Its a great scene that set Yeager on the path to fame and fortune, and it might even bring a patriotic tear of pride to your eye.

I had my first doubts about Wolfe's account when I discovered that Chalmers "Slick" Goodlin was a Pittsburgh area native, born in nearby Greensburg on January 2nd, 1923 and raised just down the road in New Alexandria, where he learned to fly as a teen (and legend has it he would sometimes deliver newspapers from the open cockpit of a plane). A real Pittsburgher wouldn't think twice about squeezing their employer for every nickel they could get, but something didn't ring true about the rest of the story: Goodlin had already agreed to make the flight - a Pittsburgher would sooner root for the Browns than back out of a deal!

So I started digging a bit more. On the Internet there are lots of stories about Goodlin's demand for $150,000 to make the flight, but most of those seem to be re-tellings of bits and pieces of Wolfe's book. Goodlin's story is harder to piece together, but I think this is pretty close.

In late 1940 with WWII well underway in Europe and the U.S. still on the sidelines, a very young Chalmers Goodlin headed north to join the Royal Canadian Air Force in hopes of making it into combat over England. Goodlin joined the RCAF on his 18th birthday, picked up the nickname "Slick" for his flying skills and made his way to England as a pilot instructor. In late 1942, well after Pearl Harbor, the Navy somehow discovered a U.S. citizen flying for the Canadians in England, and asked him to return to the U.S. to train as a test pilot. Goodlin ended up in Florida flight testing most every plane the Navy flew - and thinking being away from the action wasn't as much fun as he had thought.

And then in December of 1943, in the middle of the biggest war ever, with less than 1 year of service, Goodlin was somehow released from the Navy to become a test pilot for Bell Aircraft. Exactly how that happened is open to speculation, but it probably had a lot to do with Larry Bell.

Bell had worked his way up through the Martin and Consolidated aircraft companies, eventually becoming a vice president. In 1935 Consolidated decided to relocate from Buffalo, New York to California, and Bell took the opportunity to start his own company in New York. Bell knew lots of rich and powerful people, including General Hap Arnold - commander of the US Army Air Force (USAAF) during WWII. Arnold had seen the Gloster Meteor flying in Britian and was convinced that jets were the future of air warfare; he gave Larry Bell the job of building the first US jet and by late 1942 it was flying out of a tiny airfield in the California desert - a place that would someday be Edwards Air Force Base. Which is a long way of saying that if Larry Bell needed a test pilot in 1943, he would have no problem springing one from the Navy.

Fast forward to 1946 and Goodlin was one of a very few test pilots at Bell Aircraft, second only to Jack Woolams. Bell had a contract to build the XS-1 - a rocket powered research plane designed to break the sound barrier - in a joint project between the civilian National Advisory Council for Aeronautics (NACA) and the US Army Air Force.

The project quickly become a den of infighting. The NACA saw it as a giant science experiment; they had the planes wired with sensors and planned to generate mountains of incremental data over dozens of flights. Bell Aircraft was expecting to earn a pile of money for performing the test flights. And the USAAF, facing massive post-war budget cuts, just wanted to take over the flying as quickly as possible.

Then while the project was just starting, Jack Woolams crashed his P-39 air racer into Lake Ontario at 400+ mph while preparing for the Cleveland Air Races. Overnight, 24 year old Chalmers Goodlin became the lead test pilot for the XS-1, making a handshake deal with Larry Bell to take over Woolams contract, which included a hefty bonus for breaking the sound barrier. Its not clear how much the bonus actually was; the often quoted $150,000 figure may have included other flying Woolams was to perform - and of course there was a chance Goodlin might not live to collect it. But still it was a lot of money for 1947.

Over the next 8 months, Goodlin would make 26 flights in the two XS-1s, including the first powered flights, eventually pushing out to mach 0.8 in the spring of 1947. And then things got really interesting. In the midst of the constant wrangling over how many test flights Bell would perform, in July of 1947 the USAAF became the US Air Force. By August, Goodlin was out and Yeager was making his first flight in the XS-1. You can draw your own conclusions, but here are mine: having Air Force personnel break the sound barrier became an obvious way to give a bit of credibility to the fledgling service, and help establish the careers of the senior officers running the project. Hap Arnold had retired in 1946, greatly reducing Larry Bell's ability to pull strings, and the hefty bonus promised to Goodlin became a handy excuse for canceling Bell's contract. Even if Goodlin had offered to fly for free he wasn't getting the flight.

So if you see an X-1 on a contest table without the "Glamorous Glennis" decal take a closer look; it might not be a mistake!

A great scene - except it never really happened!

I had my first doubts about Wolfe's account when I discovered that Chalmers "Slick" Goodlin was a Pittsburgh area native, born in nearby Greensburg on January 2nd, 1923 and raised just down the road in New Alexandria, where he learned to fly as a teen (and legend has it he would sometimes deliver newspapers from the open cockpit of a plane). A real Pittsburgher wouldn't think twice about squeezing their employer for every nickel they could get, but something didn't ring true about the rest of the story: Goodlin had already agreed to make the flight - a Pittsburgher would sooner root for the Browns than back out of a deal!

So I started digging a bit more. On the Internet there are lots of stories about Goodlin's demand for $150,000 to make the flight, but most of those seem to be re-tellings of bits and pieces of Wolfe's book. Goodlin's story is harder to piece together, but I think this is pretty close.

In late 1940 with WWII well underway in Europe and the U.S. still on the sidelines, a very young Chalmers Goodlin headed north to join the Royal Canadian Air Force in hopes of making it into combat over England. Goodlin joined the RCAF on his 18th birthday, picked up the nickname "Slick" for his flying skills and made his way to England as a pilot instructor. In late 1942, well after Pearl Harbor, the Navy somehow discovered a U.S. citizen flying for the Canadians in England, and asked him to return to the U.S. to train as a test pilot. Goodlin ended up in Florida flight testing most every plane the Navy flew - and thinking being away from the action wasn't as much fun as he had thought.

And then in December of 1943, in the middle of the biggest war ever, with less than 1 year of service, Goodlin was somehow released from the Navy to become a test pilot for Bell Aircraft. Exactly how that happened is open to speculation, but it probably had a lot to do with Larry Bell.

Bell had worked his way up through the Martin and Consolidated aircraft companies, eventually becoming a vice president. In 1935 Consolidated decided to relocate from Buffalo, New York to California, and Bell took the opportunity to start his own company in New York. Bell knew lots of rich and powerful people, including General Hap Arnold - commander of the US Army Air Force (USAAF) during WWII. Arnold had seen the Gloster Meteor flying in Britian and was convinced that jets were the future of air warfare; he gave Larry Bell the job of building the first US jet and by late 1942 it was flying out of a tiny airfield in the California desert - a place that would someday be Edwards Air Force Base. Which is a long way of saying that if Larry Bell needed a test pilot in 1943, he would have no problem springing one from the Navy.

Fast forward to 1946 and Goodlin was one of a very few test pilots at Bell Aircraft, second only to Jack Woolams. Bell had a contract to build the XS-1 - a rocket powered research plane designed to break the sound barrier - in a joint project between the civilian National Advisory Council for Aeronautics (NACA) and the US Army Air Force.

The project quickly become a den of infighting. The NACA saw it as a giant science experiment; they had the planes wired with sensors and planned to generate mountains of incremental data over dozens of flights. Bell Aircraft was expecting to earn a pile of money for performing the test flights. And the USAAF, facing massive post-war budget cuts, just wanted to take over the flying as quickly as possible.

Then while the project was just starting, Jack Woolams crashed his P-39 air racer into Lake Ontario at 400+ mph while preparing for the Cleveland Air Races. Overnight, 24 year old Chalmers Goodlin became the lead test pilot for the XS-1, making a handshake deal with Larry Bell to take over Woolams contract, which included a hefty bonus for breaking the sound barrier. Its not clear how much the bonus actually was; the often quoted $150,000 figure may have included other flying Woolams was to perform - and of course there was a chance Goodlin might not live to collect it. But still it was a lot of money for 1947.

Over the next 8 months, Goodlin would make 26 flights in the two XS-1s, including the first powered flights, eventually pushing out to mach 0.8 in the spring of 1947. And then things got really interesting. In the midst of the constant wrangling over how many test flights Bell would perform, in July of 1947 the USAAF became the US Air Force. By August, Goodlin was out and Yeager was making his first flight in the XS-1. You can draw your own conclusions, but here are mine: having Air Force personnel break the sound barrier became an obvious way to give a bit of credibility to the fledgling service, and help establish the careers of the senior officers running the project. Hap Arnold had retired in 1946, greatly reducing Larry Bell's ability to pull strings, and the hefty bonus promised to Goodlin became a handy excuse for canceling Bell's contract. Even if Goodlin had offered to fly for free he wasn't getting the flight.

So if you see an X-1 on a contest table without the "Glamorous Glennis" decal take a closer look; it might not be a mistake!

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)